Review by Daniel De Lost

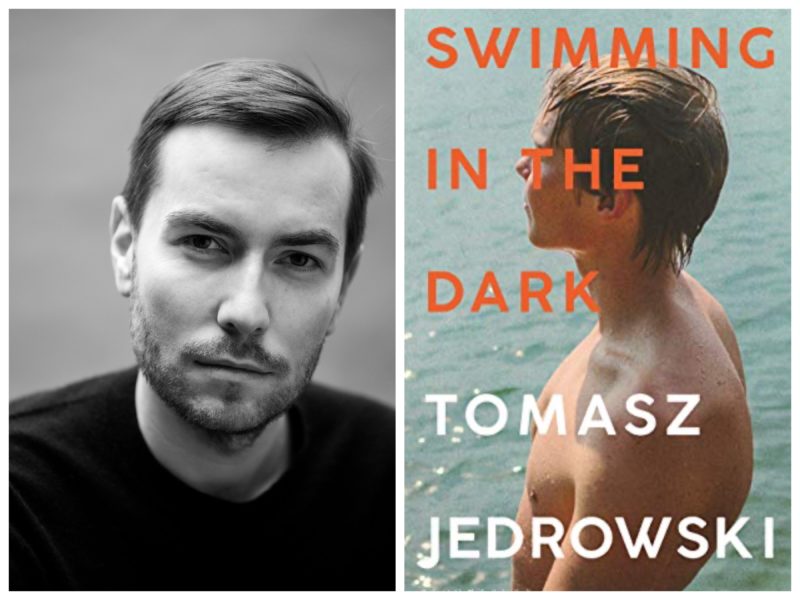

Author: Tomasz Jedrowski

Publisher: Bloomsbury

Genre: Queer fiction

Pages: 256

Year of publication: 2022

Sinopsis. You were right when you said that people can’t always give us what we want from them. Poland, 1980. Anxious, disillusioned Ludwik Glowacki, soon to graduate university, has been sent along with the rest of his class to an agricultural camp. Here he meets Janusz – and together, they spend a dreamlike summer swimming in secluded lakes, reading forbidden books – and falling in love. But with summer over, the two are sent back to Warsaw, and to the harsh realities of life under the Party. Exiled from paradise, Ludwik and Janusz must decide how they will survive; and in their different choices, find themselves torn apart. Swimming in the Dark is an unforgettable debut about youth, love, and loss – and the sacrifices we make to live lives with meaning.

Review

Coming to terms with a debut novel is always a bet. That is the case with Tomasz Jedrowski’s Swimming in the Dark (2020). When the book came out, last winter, it immediately caught the eye of queer fiction’s attentive readers: paradoxically, it is such a bleak title for a colourful and sensual book cover, as long as you don’t open it and – inevitably – turn yourself into a swimmer, moving through the rough seas of youth, deep love, fear and loss.

And what’s more, the young author is curiously Polish, born in West Germany, living in Paris and writing in English; a tangled background story which is quite enough to arouse the curiosity of readers on the lookout for distinctive new voices.

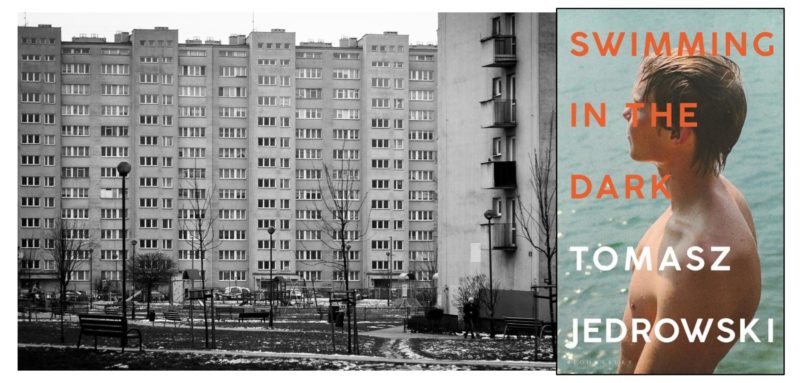

The divergent yet sometimes tightly linked spheres of politics and desire – especially when it comes to homosexual affectivity – make for doomed bedfellows in Jedrowski’s novel, an intricately structured coming-of-age romance between two young men living under the autocratic rule of the Polish United Workers’ Party in the early 1980s.

The novel is written in the guise of an open letter in which Ludwik, through first-person narrative, refers to his former lover, Janusz, in the second person as he recounts the highs and lows of their affair, as well as the ideological discrepancies that led to its end. When he begins to retrace their story, Ludwik has been in the United States as a political dissenter for a year, the same time he spent without seeing Janusz, who has chosen to remain under the oppressive communist rule, rather than risking ending up in a capitalist country he has been indoctrinated to despise.

These are good premises for an opening confession: nine years old and on a religious excursion with other fellows his age, Ludwik tells of how he developed a singular affinity with—and first real crush on—a Jewish boy named Beniek. During a party on the last night of the trip, when the lights accidentally go out, Ludwik finds himself on the dance floor in the dark, pulling Beniek’s willing body against his own. But when the lights are thrown back on and everyone can see what he’d done, he experiences for the first time the lethal combination of desire and shame.

Ludwik later comes to understand, during secret listening sessions of Radio Free Europe broadcasts with his mother and grandmother, that the Polish United Workers’ Party had risen up against Poland’s Jewish population, accusing them of the country’s involvement in the war and forcing them to flee. Ludwik’s sexuality is thus connected to politics from the start, represented in a carefully and skillfully constructed sequence of linked scenes narrating both his sexual and political development in turn. But a breakthrough occurs when he comes across a copy of James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room. He eventually reads the book himself, and he feels immediately caught up in its world.

Ludwik reads Giovanni’s Room over a course of days otherwise spent doing exhausting manual labour at a work education camp, where he later begins flirting with Janusz after spotting him enjoying a solitary swim in a river. Eventually, Baldwin’s novel becomes a connection between them, as well as it is a glaring and remarkable source of inspiration for Jedrowski’s narrative, always elegant, tender albeit its poignancy. Is then Giovanni’s Room – as well as its author – “a pander”, quoting Francesca da Rimini, from Dante’s Inferno? A possible interpretation, indeed. Just like Francesca who, after reading the story of Lancelot and Guinevere, falls desperately in love with Paolo, committing the sin of adultery – with his brother-in-law on top of that – Ludwik experiences forbidden love with Janusz, pushed by the power of Baldwin’s book; Their love is doomed to fail, believed to be a deviant behaviour, immoral as much as adultery is.

Yet Baldwin’s fictional world of pain and fear creates a shared space allowing for some possibility of love, when the two start to spend an almost dreamlike few weeks camping together in the woods, exploring the nature of desires they’d mostly kept concealed until then. But the first sparkles of strife between the two young men, who are otherwise blissfully in love, surface in conversations that enter the realm of politics.

“I should have known you’re one of them”, Janusz says when Ludwik brings up the prospect of leaving Poland for the West in search of freedom—freedom from the state, freedom to live a life full of meaning and freewill. Janusz would rather follow the rules and comply with the system, corrupt as it might be, rather than take any risk associated with rebellion. And when they return to Warsaw after their time alone together, Janusz to begin work with the Party and Ludwik seeking a possible future as an academic, the disparity between their two political views—amounting to a disparity between how they envision possible futures for themselves—only increases.

Making ideological difference the basis for dramatic conflict in a fictional narrative could be daring, since the possibility of reconciliation and resolution is completely based on the notion that characters must forsake their views—or not. But in the novel there’s little hope for Ludwik that Janusz is going to suddenly transform into a revolutionary, as he quite purposely builds a comfortable life for himself within existing constraints. And so instead of staging a political impasse between two men in love as a tragedy, Jedrowski provides readers with the pleasure of observing the development of a personal politics, Ludwik’s coming of age less a coming-out narrative than one of gradual radicalization.

Shifting from the tremors of first love to the quiet melancholy of growing up, ageing and drifting apart, Swimming in the Dark is a powerful mixture of romance, post-war politics, intrigue, and history. Lyrical and sensual, intimate and intense, Tomasz Jedrowski has given life to an unforgettable and thought-provoking first work that explores freedom and love in all its lights and shadows.

Tomasz Jedrowski

Tomasz Jedrowski is a graduate of Cambridge University and Université de Paris. He was born in Germany to Polish parents, and has lived in several countries, including Poland, and currently lives in Paris, France, where he works in high-fashion. He speaks five languages and writes in English. Swimming in the Dark is his first novel.

Acquista su Amazon.it: